Many African countries have welcomed Chinese investment, and wouldn’t you too? China has shown the world what economic growth looks like in the 21st century, positioning itself as a leading example for development. This is no more true than in Africa, where many countries have embraced Chinese technology and their global leadership in rapid infrastructure growth.

But as Chinese investment pops up across the continent, so too do the consequences of this new development model. It turns out Chinese investment comes with a high price, one that cannot be paid off with bribes or by simply turning a blind eye.

The Shift Towards Chinese Investment

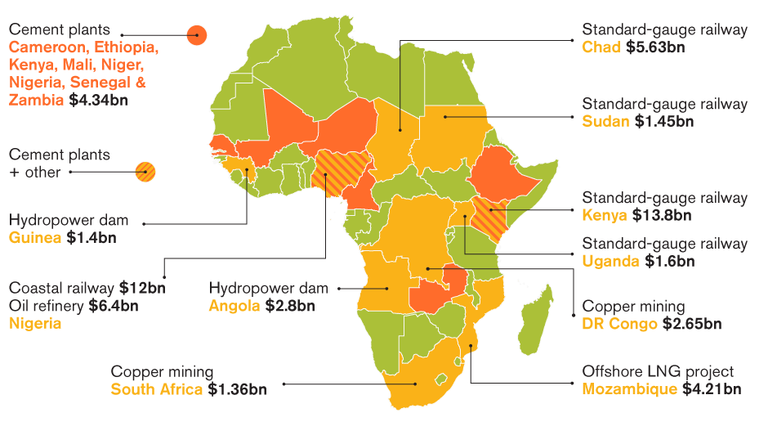

At the 2021 Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, the President of the African Union Congress praised China, calling for its leaders to recognise China’s ‘hands off’ approach to levelling up the continent. And it’s true, Zimbabwe, Kenya and many more have turned to China’s efficient technology and impressive history in building massive infrastructure projects at record pace. And these projects have been no small feat, ranging from rail systems to energy plants.

This has been a deliberate foreign policy employed by China to step in amidst growing tensions concerning political conditionality, traditionally tied to Western aid. China offers the ‘Eastern’ alternative, not interested in political malarkey or, as they put it, neo-colonialism, just as long as the African government guarantees logistical and, most importantly, financial collaboration with Chinese state-run companies for these multi-million-dollar projects.

Win-win, right? Local governments get to skip past the addressing corruption chapter of the Western development lecture and China’s Belt and Road Initiative keeps ploughing along throughout the African continent. Not quite. Since 2018, Angola has been the only Sub-Saharan African country to improve its score on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. The Chinese led development is bolstering corruption, eroding steps towards good governance and ignoring the commitments required for sustainable development in Africa.

It’s a calculated attempt to weaken external checks and balances for both parties involved, not just to ignore corruption, but to milk it’ structures whilst they last. Direct aid delivery without the involvement of non-governmental organisations, civil society and other important means of accountability normalises corruption through supposedly rational arguments of prioritising economic growth and short-term prosperity. It paints the picture of corruption as an inevitable outcome of economic growth and development partnership that doesn’t fall at the first political disagreement. This is simply not true. Whilst attractive and perhaps the only viable alternative to Western development so far, the Chinese development model doesn’t do enough to take steps towards locally-led, long term development that can outlast competing development models or foreign policy brawls among the latest superpowers.

So who is to blame? Is it local governments for their eagerness to bypass preferential, even at times excessive, good governance requirements for Western aid, or is it China’s blindsided alternative to development that waves through corrupt standards? Or perhaps it is the very root of the problem, an inadequate development model that fails to take into account local nuances and regional needs. It’s probably all three, but it cannot be replaced by development that by passes legitimate checks and balances, that confront corruption for long-term sustainable development, even when it hides behind persuasive economic arguments.